I've been haunted a lot by a ghost these past few days – not one of those terrifying Hollywood ghosts, nor a cutesy friendly children's ghost either.

The ghost I've been haunted by is the sort who makes you stop consider how well we are meeting the challenge of our times, compared to how well the ghost faced theirs. When this particular ghost was still alive, there was a war on, and his country needed him. Eleven states in the South, fearful that the president would abolish slavery, had declared themselves free and independent of their brothers in the North. So one morning he got up, kissed his mother and father goodbye, and left the Pennsylvania farm he had known his whole life.

He is an ancestor of mine whom I've only known through a family legend. As his ghost has drifted through the house, I have wondered at how little I know about him. Did he enlist because he had a moral conviction that the Union must be preserved at all costs, or was there another reason? Did he think the war would end soon, or was he expecting to be away for years? Did he ever wonder if it would be worth it in the end?

To tell the truth, until recently I didn't even know his name. All I knew was one horrifying detail of his life.

“I have an ancestor who was a prisoner of war at Andersonville,” I once told one of my best op-ed columnists. Marc Kelley wrote for the Cranford Eagle while I was its managing editor, and also worked as a Realtor in the downtown.

“Did he survive?” Marc asked. “That was an awful place, you know. The commander of that camp was the only Confederate officer to be executed for war crimes after the Civil War ended.”

“He did,” I said, “and it's a good thing for me, too. After the war, he went on to get married and have children.”

That was all I really knew about him. For the longest time, I assumed he was a Learn, since I knew he was an ancestor on my father's side. A few weeks ago an email from my father set me straight. His name was Samuel Bowman, and he was the father of my Grandmother Ruth Learn's father.

With a little searching, I was able to find an online database of records pertaining to the Civil War, including a list of POWs at Andersonville, more formally known as Camp Sumter. I'd checked before but had been unable to find anyone named Learn in the database. Now that I had the right name, I went back to see what I could find. It wasn't encouraging.

According to the database, a Pvt. Sam Bowman died on July 20, 1864, while held at Camp Sumter in Andersonville, Ga. The cause of his death is listed as diarrhea. No other information was listed, aside from his unit — 147th New York Infantry, Company H — which told me nothing. Most likely Pvt. Bowman was buried in one of several mass graves on site.

The snippet of genealogy my father had included in his email mentioned that Samuel Bowman, born in 1842, had enlisted in the Union Army with his older brother James "J.J." Bowman. It also reported that Sam and his wife had one child, a son.

The Andersonville records do not list a James Bowman, who is buried at the Cambria Mills Cemetery in Fallentimber, Pa. I assume that J.J. made it home after the war had ended, and I hope that he lived a long and happy life with his wife, Eliza, and however many children and dogs they had.

But Sam! The story of his family seemed too painful even to consider. If he died in 1864, Sam couldn't have been more than 22 when he died. Was his wife already visibly pregnant when he left, or was she not yet showing? Did they even know?

Maybe their son already was born. Just imagine the tableau: She stands there in the early morning as J.J. and her Sam leave together. As she watches him go, never to return, she cradles their young son in her arms, or maybe feels him tug at her dress from where he stands next to her on the porch.

It's easy to picture her, young face darkened with foreboding; and just as easy to imagine the grief that would have pierced her heart when news came that her husband had died. She would never take another husband. When her son became a man himself, he married and continued the Bowman line. Picture the single mother, raising her son with the help of her late husband's family, reminded daily of the man she had loved as the son he had left her grew daily into his likeness.

But then, history smiled and I was pleased to discover that my original story was more correct. There was more than one Samuel Bowman at Camp Sumter. Pvt. Bowman died, but my ancestor Sam didn't.

When Sam left Camp Sumter and made the long trek home, he stopped along the way and courted Elizabeth “Fanny” Swain, and married her. They had one son, whom they named Edgar and raised together. When the time came, Edgar married May Cartwright. Together they had four children of their own, the second of whom was named Ruth Virginia Bowman. She was my grandmother.

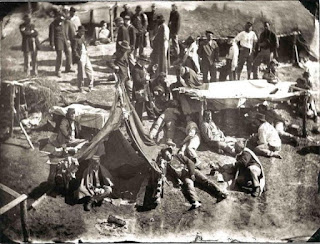

Of the approximately 45,000 Union prisoners held at Camp Sumter during the war, nearly 13,000 died, primarily from scurvy, diarrhea and dysentery. When rescue finally came at war's end, the prisoners' deliverers described them as skeletal, emaciated, and covered with filth and vermin. There are pictures on the Internet. They could just as easily be pictures of Holocaust survivors.

As Marc had told me, the general pardon that President Lincoln extended to the rebel soldiers at the end of the Civil War did not extend to the commander of Camp Sumter. The record shows that Capt. Henry Wirz was tried and hanged for war crimes, the only Confederate official to be so tried and convicted.

(To be fair, some historians dispute that Wirz was responsible for the conditions at Camp Sumter, and instead blame the overcrowding and infectious disease, both due to circumstances beyond his personal control.)

In many ways, Sam Bowman is the perfect ancestor at a time like this. Like Lincoln, Gen. Ulysses Grant strode through his time like a titan. By dint of his position, his character and his drive, he moved the river of history from one bed to another. Claiming him as ancestor would be an exercise in vanity, like trying to make myself better by the association. Sam, on the other hand, was a nondescript nobody from central Pennsylvania.

My great-great-grandfather saw the end of the Civil War and the assassination of Lincoln. He saw the nation quit its half-hearted attempts at Reconstruction, and may have heard about the rise of jim crow justice and how by brute force the resentful South undid much of the hard-won work the Union did in liberating the slaves.

Sam may even have heard stories about the Great Migration as blacks fled a reign of terror in the South that would have put ISIS to shame, and ran North to places like New York and Chicago in the hopes of life, liberty and a future.

I only can imagine how he'd react to hearing that the Republican Party, once the Party of Lincoln, had forsaken that heritage and descended into what it's become now; and how it had elected a man as unstable as Donald Trump and so openly racist that the Ku Klux Klan was celebrating his election as their vindication.

Sam Bowman fought to save the Union. I'd hate to think of what he'd say to see it now, and I wonder how he would fight to save it again.

Copyright © 2016 by David Learn. Used with permission.

Tweet

No comments:

Post a Comment